The Pashtun nation must certainly have many flaws, as every country does, and we have been discussing them from time to time. No nation is entirely perfect, but this does not mean that there are no virtues or positive aspects in the Pashtun nation.

Sadly, the Pakistani media and production houses have always portrayed the Pashtuns in a one-sided manner, in which only their negative aspects are highlighted. This attitude has not only distorted our identity but has also solidified an unbalanced and negative impression in the minds of the new generation.

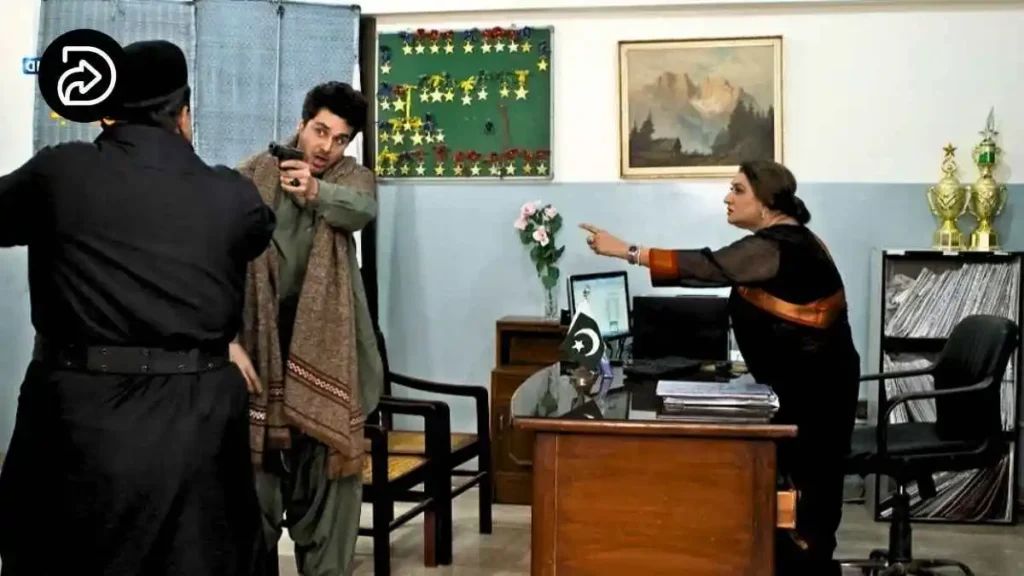

Meray Humnasheen Episode 22: Pashtun Identity and Pakistani Dramas

Our main objection has always been to this style of portrayal. If a nation is depicted in a drama or film, justice demands that both its positive and negative aspects be presented. However, unfortunately, this balance is often missing in Pakistani dramas.

This issue has been ongoing for many years. Countless dramas and films have been made, but show me a single scene in which any positive aspect of the Pashtun nation has been presented without exaggeration and extremism.

See this Short Film to See How a Pakistani Director shows Pashtuns in Pakistani Dramas.

Whenever a Pashtun character is depicted in the dramas, they are often stereotyped into a particular mould. Either he is a brutal, angry bully or an ignorant person, or simply a background character who does not exceed the limits of a watchman, driver, or laborer.

However, the reality on the ground is the opposite. At every critical stage of Pakistan’s history, in every field, Pashtuns have made their sacrifices, rendered services, and achieved remarkable achievements. From the army to the judiciary, from education to science and technology, from literature to the field of play, it is impossible to deny the presence and services of Pashtuns.

If production houses are genuinely keen on representing the Pashtun nation, then their inner aspects should be portrayed in a genuine and balanced manner. Language is a fundamental part of a nation’s identity and culture. Pashto is not just a dialect, but a culture, a history, and a feeling.

There are countless capable, educated, and talented actors in this nation. If a Pashtun character is to be portrayed in a play or film, these actors should be allowed to represent the character authentically, incorporating their accent, language, and behavior.

By using such broken Urdu in these characters, the intention is only to prove the Pashtuns ignorant. This becomes a question mark on the intelligence and dignity of the Pashtun nation. Its purpose is only one: to prove the nation weak, uncivilized, and incompetent, so that an atmosphere of prejudice and hatred is created against them among the rest of the people.

This behavior is not just a part of art, but a well-thought-out propaganda. When a particular nation is constantly portrayed in a negative way in the media, it also has an impact on social attitudes. This discriminatory narrative then comes to the fore in the form of prejudices, hatred, and racial discrimination in everyday life.

We must not only defend our identity and culture, but also speak out against the prejudices that are being spread against us through the media. It is time for us to collectively challenge these narratives and present our true identity to the world as a brave, educated, respectful, and talented nation.

What hurts the most is not the criticism itself, but the silence that follows it, the silence of those who know the truth but choose to look away. For decades, the Pashtun nation has been watching itself through someone else’s lens, a distorted, narrowed view that hides its grace, its intellect, and its kindness. The tragedy is not only in being misrepresented, but in being consistently misrepresented. When you are reduced to a stereotype for too long, even truth begins to lose its voice.

The image of a Pashtun on television, loud, angry, violent, is not a reflection of reality, but a reflection of the ignorance that still dominates our creative spaces. The same nation that produced poets like Khushal Khan Khattak, philosophers like Bacha Khan, and countless scholars, soldiers, and thinkers, is now being portrayed as backward and uncivilized. This disconnect between who we are and how we are shown is not just offensive; it is heartbreaking.

I’ve spoken to Pashtun students in Lahore and Karachi who admit that they often hide their accent in classrooms. Some change their names on social media to avoid judgment. Imagine the kind of pain it takes for someone to erase a part of their identity just to feel accepted. This is not what art was meant to do. Art was meant to unite, to humanize, to give a voice to those who are unheard. Yet our screens have turned into mirrors that reflect prejudice instead of empathy.

If Pakistani media truly wants to show the diversity of this land, it must begin by revealing the truth, not caricatures. Every Pashtun is not a tribal extremist, just as every Punjabi is not privileged, and every Baloch is not rebellious. We are all parts of one collective story. To tell one group’s story honestly is to honor all of Pakistan.

Representation is not just about putting a Pashtun face on the screen; it’s about showing that face with respect. It’s about showing a father who works hard, a daughter who studies medicine, a poet who writes in Pashto and Urdu, and a teacher who believes in peace, because these are also the faces of the Pashtun nation. There is pride, there is sacrifice, there is compassion, all waiting to be seen beyond the smoke of stereotypes.

It is time we ask why a nation known for its hospitality, bravery, and loyalty has been painted in the color of fear. The answer is simple because no one fought hard enough to control the narrative. Now that responsibility falls on the new generation of Pashtun writers, filmmakers, and students to reclaim that story. To tell it in their own language, through their own voices, with their own truth.

We don’t want sympathy. We want fairness. We don’t ask for glorification. We ask for honesty. Every nation has flaws, and the Pashtun nation is no exception, but reducing an entire culture to a single shade of negativity is not critique; it is cruelty.

In the end, the call is simple: portray us as we are with our strengths and our struggles, our humor and our heartbreaks, our flaws and our faith. Because behind every Pashtun face there is a story worth hearing, not fearing.

Let the next generation see themselves on screen not as villains or victims, but as humans proud, complex, and full of dreams. Let art once again become what it was meant to be: a mirror of truth, not a mask of prejudice.